Levitating With Footy: Helen Garner’s The Season

Part of my Readit series in the Prom Coast News

In a Helen Garner book, people cook and scoff, play music and wander arm-in-arm, weep and tidy, bellow and say things they do not mean; listen well and poorly, choof and dance, chiack and argue, pedal and surf, panic and screw. And die.

In The Season nobody dies. After years witnessing autopsy, murder trials, and watching theatre, here you find lightness. As with other artists clearing their 80s, you no longer need to become somebody.

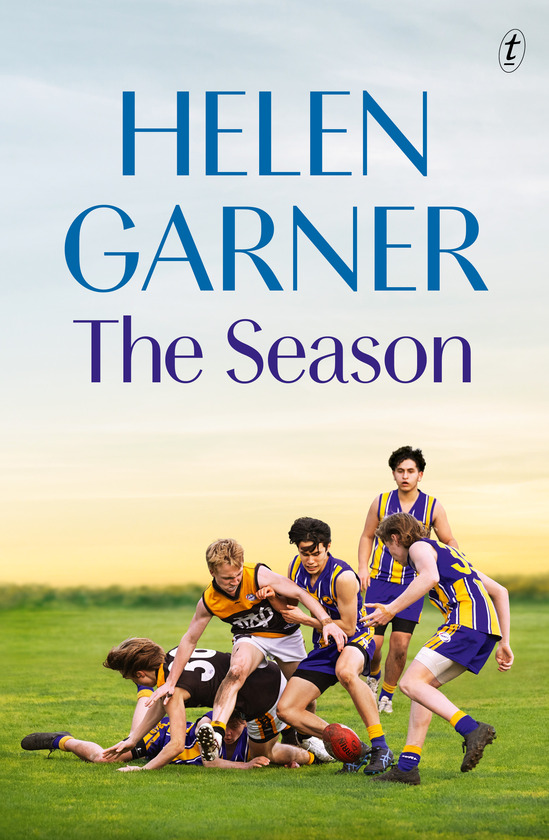

People get hurt. This is the story of Helen Garner’s year following the Flemington U16 Colts, and her grandson, ruckman, Ambrose, interleaved with the fortune and fate of the AFL Western Bulldogs.

So, scrappy. There are even references to long-term head injury, but only to run from it, as she runs from stats and the game’s history and politics.

The kind of injury Garner’s heart catches on is a boy’s tumble, boot stops in the thigh, broken leg. Garner’s partisan response to a Collingwood injury is shamed by another grandmother. Pain is complicated here, tackling a skill and a desired violence, their coach’s prescription of running after a loss no punishment but a necessary source of winning strength, moving on.

And there’s plenty of violence. Our game’s fighting immediacy, joyous battle sublimation and youthful passion at one end, and its place in the week and family at the other—this is The Season’s subject.

If it’s not the sacred nature of sport. Helen Garner doesn’t pretend to know football but she does get the wellsprings of culture and Australian life. A netting bag of oranges and gin bottle in The Children’s Bach, cycling past nighttime Melbourne Exhibition Buildings in Monkey Grip, and now player and parent melee and being halftime oranges nanna.

Garner’s feeling of some presence beyond us dates back to Cosmo Cosmolino and maybe earlier; I disagree that atheists may not feel it and yet in Garner’s honesty about her desire for more, more, than this, she has opened the space to utterly nail it. AFL especially is an art reaching skyward, like ballet; yes its ideal bodies are large, but light with it, long as greyhounds and lithe as KG whiting. Some young women here do compare netball with footy, but glancingly, and Garner doesn’t rouse code or state beasts; here we see footy as jazz, acrobatics, spectacle—and worship. This isn’t woo-woo profundity, at last she shows the bricks: putting your body on the line; in the zone making out play under winter dark; young energy and love and growth pain; crowds “beserk” for their messengers of the gods. The roots of it in family routine and fitting in training no matter how sore or wet or freezing. Loss.

Brotherhood. In sports “literature,” replacing the male-unsporty-geek-foreigner-journalist with gimlet-eyed-feminist-nanna-opera-buff does make a change, nevermind Garner omitting entirely she’s a national treasure—that’s of a piece with our hero’s wildly creative parents as merely Amby’s mum and dad. There’s open envy for garrulous, beautiful boys—striding, ambling, buffeting, slinging, twriling, milling—and a casual absence of self-pity about her coming years, an approach which allows us to accept this as a new angle on masculinity in a world with plenty of male ones.

Also, it’s beautiful poetry.

How many artists go on at the height of their powers into their 80s? Alright, Saramago, Atwood, Miró, Le Guin, Keneally, Glass, but it’s uplifting as a writer to see that the good dying young doesn’t mean the rest of us are old tossers. This Garner shows promise. I look forward to her next book. (She’s not ruling it out.)

| The Season | Helen Garner | Text Publishing | 208 pp | 26/11/2024 |